With the 101st edition of the Tour de France due to begin on Saturday and a summer of sport well underway, I believe the time is right to delve into the past and look to when the world’s greatest cycling race crossed the channel to our shores. On the 7th of July 1994 Hampshire was gripped with cycling fever; a 187km long 5th stage was about to begin and end in Portsmouth. Half a billion eyes around the world were glued to television sets as the peloton, which included cycling legends Marco Pantani, Miguel Indurain, Chris Boardman and a young Texan named Lance Armstrong, powered past HMS Victory in the Historic Dockyard. For a day, Portsmouth played host to one of the most prestigious sporting events on the calendar. So how did this extraordinary day come about? In a two part post, I catch up with Southsea resident and ex-council employee John Bagnall, a key player in bringing the event to the city.

Hi John, thank you for taking time out to speak to us. First of all can you tell us what you were doing during the lead up to 1994?

I was the Marketing Communications Manager at Portsmouth City Council, it was looking after press and media relations.

And I believe that this whole venture arose from a discussion over a pub lunch, is that right?

My colleague David Knight, head of leisure for the city council said to me “What can we do that will really put Portsmouth on the map and be a counter point to the D-day commemorations? What is international, bright, young and youth orientated?”

So when you say the commemorations? This was the 50th D-day celebrations? Quite a big deal.

Yes, it was the 50th anniversary of D-day. So for a week at the start of June, Portsmouth became centre to the world in terms of commemorating the liberation, or the beginnings of the liberation of Europe. Clinton and the Queens were here, many world leaders came to Portsmouth and stood in a special bandstand built on Southsea Common. There was a huge international flypast, I think a couple of hundred planes came over Portsmouth; Spitfires, Lancaster Bombers, Flying Fortresses, it really was the world solemnly marking D-day and the beginning of the end of World War Two.

OK, so press-wise, a pretty good window of opportunity here. What was discussed over lunch?

As I said to David over that pub lunch “Hey, why don’t we bid to get the Tour De France to England?” I’d never really thought at that moment there was a realistic prospect of getting them here, I just thought the council would probably laugh it out of court anyway. Even if we did get as far as sending an invitation to them they would just turn round and say “I’m sorry, why would we come to England? You have no history or heritage of cycling”.

So to add a little context, I believe The Tour had come to England once before? In 1974?

Yes, the time before they raced on the newly completed, but not yet opened, Plympton By-pass near Plymouth. It was just coned off at each end and they went up the dual carriage way for X number of laps. And that was it. I think a few hardcore cycling clubs came to see some of the riders of that time, but there was no broadcast coverage and precious little coverage in the newspapers. By all accounts it was very dull and very boring. The Tour didn’t like it because of the amount of time it took to get the riders there and then take them back again.

I see, so it seems like The Tour organisers weren’t exactly scrambling to recreate another UK leg?

No, the tour had no thoughts of coming to England ever again after the Plymouth stage. So during that pub lunch the idea really was to “fly a kite”, let’s do something a bit crazy. My argument to David was; they will probably say no even if they bother to reply, but I can still get some publicity out of that. Perhaps a little story into the cycling friendly The Guardian about how a town in Portsmouth bids to get France’s biggest sport event there (wry laugh)… So David and I went to talk to a guy called Richard Tryst who was the chief executive of the council. Richard was quite a frightening man with a hawkish and cynical sharp manner, but he didn’t suffer fools gladly. He liked boldness and directness. We went to see him and basically said “it’s crazy but we think this is a good thing to do, it ticks all the boxes of what the council are looking at”. He sorted of nodded and said “well yes, there are a lot of other questions to answer as well, but we’ll keep this alive”.

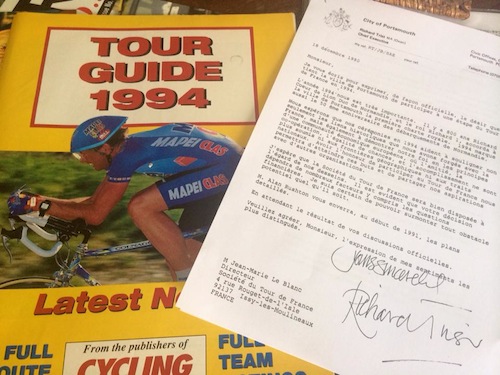

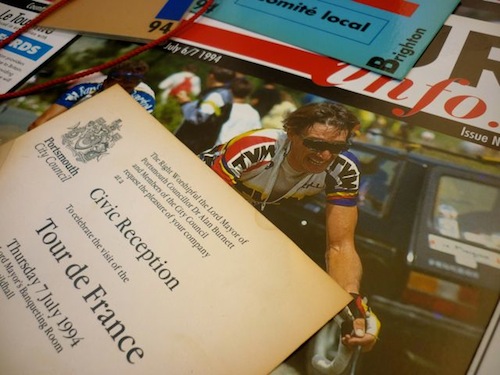

Richard bought in the then leader of the conservative council, a guy called Ian Gibson, who like all local politicians that get to be leaders of the council, was a very upfront, bold and visionary guy. And he got really excited about it as well. So on the 18th of December 1990 I drafted a letter to Henry LeBlanc who was the president of Amaury Sports Organisation, which was the company that controls the Tour De France. And about two weeks later they came back basically saying; “Subject to commercial confidence we are interested, and we are very grateful for your support”. They went on to explain that the Tour at that time was losing direction as the Tour De France; it had this great tradition attached to it but it wasn’t going anywhere with it. What they were trying to do was to introduce a policy that they called “mondialisation”. The organisers wanted to take it global and they were actively looking for other European countries that they could go to. They even discussed the possibility of, and this was back when people were excited by Concorde, to go across the Atlantic and even starting it in America or Canada. So to have an approach from an English city saying “what can we do to help?” was brilliant to them.

Could you perhaps detail some of the ins and outs of trying to organise an event of this scale whilst remaining compliant with the confidentiality agreement? Seems impossible to me.

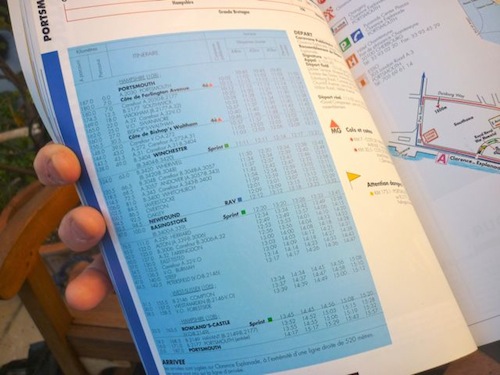

We had to sign legally binding documents with them not to divulge the fact that they might be coming here, and from there it became a planning operation. The organisers want to be able to book up every hotel going within, in some cases, 50 to 60 miles of a particular stage town. And at a competitive rate too. If it was common knowledge that the Tour was coming to Portsmouth every hotel in Hampshire, Sussex and Dorset would be ratcheting up their prices. Not only that but we had to make sure that the public knew where to be and what they were going to see. We took care of safety and we made sure there were no embarrassing blockages such as level crossing gates being down. It was a massive planning operation that went into incredible detail; and day after day more and more levels of detail were added.

Could you perhaps detail some of the ins and outs of trying to organise an event of this scale whilst remaining compliant with the confidentiality agreement? Seems impossible to me.

We had to sign legally binding documents with them not to divulge the fact that they might be coming here, and from there it became a planning operation. The organisers want to be able to book up every hotel going within, in some cases, 50 to 60 miles of a particular stage town. And at a competitive rate too. If it was common knowledge that the Tour was coming to Portsmouth every hotel in Hampshire, Sussex and Dorset would be ratcheting up their prices. Not only that but we had to make sure that the public knew where to be and what they were going to see. We took care of safety and we made sure there were no embarrassing blockages such as level crossing gates being down. It was a massive planning operation that went into incredible detail; and day after day more and more levels of detail were added.

One of the first things that came up was that the Tour uses a massive bandwidth of transmission frequencies. Back then, before radios were used with the riders, the teams still had their private frequencies so that the Director Sportif could talk to the team cars and any other helpers he needed to contact. The race officials too needed an overall race frequency that everybody could listen to, as did the aid operations, the radio operations, the feeding operations, the signing operations and for the clearing up of the signing operations. The list just went on and one. Hundreds of frequencies and sod’s law would have it that was the most of them were in the band of frequencies used in the UK for hospital radio paging systems. There was no way that we could bring the Tour through with hospitals being disrupted and lives being put at risk because of radio interference.

Immediately we set up a meeting with a government agency called the Radio Communications Agency. This was a formal meeting with about 30 of their wise men. We bought over the communications manager of the Tour and a specialist from France Telecoms. During the meeting’s presentation you could see various people around the table shaking their heads; “impossible”, “far too hard”. But a couple of the right senior people listened intently, and one of them I think the deputy chief executive said “well look, I have no idea how were are going to do this because it will be a massive problem, but leave that to us, if we can’t solve it we shouldn’t be doing our job, we think we can do it.” Suddenly the head shakers were agreeing. We got their commitment. From then on the RCA also undertook all that was necessary to make sure that the hospitals, for those two days, would be working from a different wavelength and there would be no clash.

Another major issue was that the overall physical envelope of the Tour is massively more than just the peloton. You have the advanced publicity caravan, you have the people who would have gone over two or three days prior: putting up signage, checking access to the routes, checking where they can take off vehicles that might break down. All the kind of technical aspects. They are physically working several days, and perhaps hundreds of miles distance, from where the Tour is at that particular point. It is all part of the live event. Then you have the security operation that physically surrounds the tour: the motorbike marshals that escort the official’s cars, that monitors the press and first aid cars. They have their own radio frequencies and take up physical space on the roads. Amongst those you have the camera bikes that are filming the close-up of the derailleurs and the break-aways. They are beaming a signal up to a helicopter above and there will be four to five other helicopters covering the breakaways and the peloton. Each group of cyclists needing their own cameras.

For two days they would have to touched on Gatwick’s airspace and the approach path for Heathrow. I remember being in the office when Alan Rushton called Directory Enquiries (this was pre internet days) to get the number for the Civil Aviation Authority. He phoned up the switchboard and asked to speak to whichever department was responsible for closing the airspace above British airports. You could sense the stunned silence on the other end of the phone. Thankfully the CAA came back very quickly with a can do attitude. The only stipulation being that any emergency aircraft landings would have to take priority, but otherwise they would work with the French air traffic specialists to bring the Tour through safely.

We discussed what it takes to begin paving the way for a Portsmouth stage. What else did you have to organise or overcome on your road to June 1994?

The next obstacle we had was the police, mainly due to the fact they had never dealt with anything quite so big before. At the time you had the Milk Race and the Kellogg’s Tour Of Britain as the biggest cycling events in the UK. And those were done by rolling road closures: a police car or motorcycle in front and behind which leapfrogged each other to stop the traffic. The Tour wouldn’t contemplate that, it had to be a completely sterile loop. The police have an organisation called ACPO (Association of Chief Police Officers), that oversee combined or national large scale operations. We got assigned an inspector who was a bit full of himself and quite jack the laddish. You could see why he had gone far in the police force; a rather strong personality. He came to the first meetings saying, “well you know, I can’t see it working but we’ll go through the motions”, it was that sort of attitude. This was partly because, to start off with, they couldn’t get their mind round what the Tour was and how it felt to be part of it. So we took him and a couple of his deputies, including another guy assigned by Hampshire Constabulary, to France the next year to see the race. The Tour kindly decided to put them in their control car as guests, and for two days they were able to experience their operations first hand.

Unfortunately we thought we’d blown it on the first day. By then they were into the mountains, and this particular stage finished at Sestriere in the Alps, which is one of the very famous climbs if not one of the very legendary ones. Sestriere is now in all of the record books because Claudio Chiapuccino won it with the longest by distance and time break away in Tour history. Claudio came in forty five minutes ahead of the rest, it was quite an incredible ride, and probably drug assisted at the time if the truth be known… But Sestriere is a mountain top and it was just gridlocked. There was no way you could get anywhere for hours afterwards and yet we were supposed to collect these ACPO guys in order to look after them. We just couldn’t make the physical connections. Mobiles were very new technology and there was no coverage on the tops of the alps, so we had no means of getting in touch with them. We thought we had really blown it, they will be pretty hacked off at being left stranded with French men. As it turned out our French counterparts realised the situation and said “don’t worry, we will look after you”. They dished up a really nice dinner, got them suitably drunk and they had a really good time. When we met up with them the following day we fully expected them to pull the plug on the whole affair, however they expressed a different kind of concern; “After what we saw yesterday I’m not sure that we, the English police force, could manage something so awe inspiring. It was so well organised, it is going to give us real problems matching it”. Thankfully this soon became an ego thing and before we knew it, the challenge had been set to do it better than the French.

I recall in the first half of this interview you briefly mentioned the issue of legislation having to be created specifically for the Tour, could you give us more details on what had to be put into place? What the police soon realised was that road cycling at that time, took place under a minor clause-of-a-sub-statute-of-a-bit-of-legislation dating back to 1948. This simply didn’t give them the powers they would need to create a completely sterile road closure. The existing legislation meant that it was okay for a police car to stop and for a policeman to halt traffic with his hands for 15 minutes, but not for a full day. So we shaped and drafted an Act of Parliament that was taken through as a private member’s bill. It was very discreetly done because this was still subject to confidentiality, all very hush hush. The bill went through Parliament and was enacted; giving all the relevant authorities the power to do whatever necessary to close the road and such like. This is the same legislation under which the Tour can take place in Yorkshire on Saturday. That then just left all the towns and villages. We had numerous meetings with the county councils: Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex and Hampshire because the Tour want money to come. To be a start of finish town back then was around £100,000.00, which is quite a lot of money. And that was just for the Tour to come, so not including your organisation costs. All of that had to be negotiated through all of the various councils, but I think we had the political network working for us, everyone at Portsmouth City Council was up for it. By then a momentum was gathering and rumours started to appear. Cycling Weekly would phone up every so often and ask “what is going on?” “well what do you think is going on? I haven’t heard anything?”, all this bluff and counter bluff. Cycling is a small world, so they recognised that if they blew it then it could lift the lid on the whole thing. They were bound into it as well. Gradually we ticked off all the councils putting up the money for physical improvements. After this operation had been put into place the roads on the planned the route had never better for cycling; whole stretches were re-tarmacked because none of the councils wanted to be known for having bought a rider down.

The next part of the operation was to simply identify all the businesses that would be affected; banks, supermarkets, retail outlets, etc. Staff would have problems getting in due to the roads being closed at five in the morning. Deliveries would not be able to take place and cash points would not be refilled. Memorably I researched every crematorium, cemetery and undertakers on 25 miles either side of the route in order to write to them saying “please be aware that on this day restrictions will be in place and you might not have access for mourners, don’t book funerals for that day”. Similar to this, part of the route was going up Ditchling Beacon where a very rare orchid grows, so rare that its location is kept a secret. Naturally the Environmental Agency were worried about it, so the area was coned off and marshal placed there specifically to protect this plant from cycling fans and plant collectors alike.

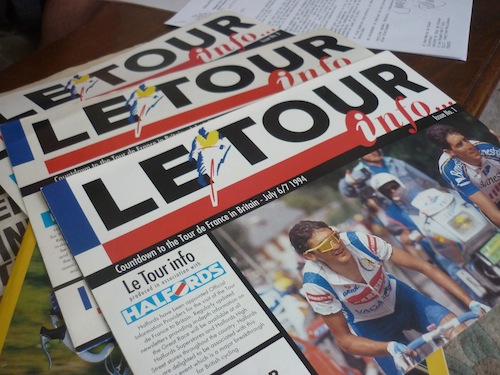

Then it was just down to getting people along the route to buy into it; we persuaded villages councils and the Department for Education to allow schools to close for the day so that their pupils were able to watch the race. By the time we had the national launch, Cycling Weekly was planning events and their editor, Martin Ayres, came on board on a freelance basis to help with the writing of our newsletter. Through our newsletters we were having to inform people who had never heard of the Tour de France what it was about. We had to get out there and convince the people who, not only did not cycle, but disapproved of cycling in general. All whilst keeping the cycling clubs and the aficionados happy. It all came together amazingly well, but it was a lot of hard work. During the winter of 93 -94, for three to four nights a week I was in village halls somewhere along the route; showing a film and telling people what would be happening. Often you would get people sitting there with their arms crossed saying “why should I pay my rates so that French men can race bikes past my house?”, we were dealing with that sort of mentality.

By all accounts this was a successful stage, but can you tell me if there were any incidents that you had to deal with? With that amount of people massed together surely some issues cropped up?

The only incident in the whole thing was during the Portsmouth leg, when a child stepped out onto the curb after the peloton came round. Unfortunately he was clipped by the wing of one of the official’s cars who were following the riders, and momentarily we were quite concerned. Thankfully the Tour stopped one of its medical cars and called up one of their helicopters. The helicopter landed just behind where it happened and took the child and his mother to the hospital for the check-up. He had a headache and was slightly bruised but nothing serious. In truth it was fantastic PR on the Tour’s part to of done that, it added hugely to the concept of goodwill.

Over the two days, the police estimated between two and three million people had watched at the roadside. It had huge television coverage relative to the time, I remember Mr Leblanc saying that we have already seen the biggest stage crowd for the whole Tour, and we were only on stage four and five. The goodwill that was generated was just amazing, it’s fantastic anywhere you go on the Tour anyway, but the friendship and fun that was being had was truly magic. It laid the groundwork for the Tour to come back to England.

What would you say the aim was in bringing the Tour here, and what legacy did it leave? What do you think it brought to the city?

The immediate aim was to inform as many people as possible across the world, that there is a city called Portsmouth on the south coast of England. A city with an important heritage and history. A city that is open for commercial business. We were the people that started this whole thing, we are a city with a “can do” spirit. We are international and friendly. This was general promotion of sorts, for all kinds of different reasons and messages, and we very much hoped to ignite greater interest in cycling. Not to mention greater investment in cycling on the part of the city. We are on an island, the highest point in Portsmouth is twelve meters above sea level, it’s difficult to think of somewhere better, perhaps Cambridge apart, in physical terms for cycling. And yet the provision within the city is not good. Unfortunately I think Portsmouth just didn’t managed to capitulate on the immediate legacy of the Tour to achieve a tipping point that could be built on. In a way that you could argue that London has done with the Boris Bikes. There is still more work to do and I don’t entirely see who is doing it and where it is coming from. Southsea Cycle Club and various community projects are doing a great job in making it visible, but I don’t think it’s really come together as a critical mass in Portsmouth.

What really makes me sorry is if you cycle up of down the back or Portsdown Hill, you can see where the cycling tracks have been laid and marked out, but the tarmac has almost worn off. There is just the faint trace of a bike as you come up from Waterlooville and I think that is ever so sad, it’s symbolic of the tokenism that prevailed in the end in Hampshire and Portsmouth. They were given an opportunity to make themselves famous permanently in England as the cycling city, but the momentum was never really achieved in the first place. It was a very successfully stage and I think the longer term legacy wasn’t in the immediate benefits to the people who ride bikes in Portsmouth. However, to the cycling community in Britain as a whole it has had enormous benefits; it worked by laying one of the first foundation stones in what you could describe as a cycling wall. In the next course of bricks above Portsmouth 1994 you have Dublin in 1998, and then a couple courses of bricks above that you have London in 2007. Next you have smaller bricks above that: Mark Cavendish and Bradley Wiggins. Riders who, as kids, might of watched Portsmouth on Channel 4. I would love to know if Mark Cavendish did and whether it fuelled his desire to be part of such a legendary event. You cannot quantify this part of the legacy. By this weekend, Yorkshire 2014 will be at the top of the wall. Yet when you look closely; Portsmouth is still right there at the bottom, as a foundation stone. This is where it all began.

Anders Bohea

20 October

I remember seeing them go down Farlington Avenue